Following the previous article on the far left/right coalition government in Greece, I was asked to provide more comments on the connections between SYRIZA and Russian fascist Aleksandr Dugin.

First of all, a few words about Dugin himself (interested readers will find my longer piece on Dugin here, and a thesis on him by my colleague Andreas Umland here).

Who is Dugin?

Dugin's ideology is called Eurasianism, but experts prefer to use the term "Neo-Eurasianism", because Dugin's ideology has a limited relation to Eurasianism, the interwar Russian émigré movement that could be placed in the Slavophile tradition. Rather, Neo-Eurasianism is a mixture of the ideas of French esoteric René Guénon, Italian fascist Julius Evola, National Bolshevism, the European New Right and classical geopolitics.

Dugin attempted to enter Russian political life twice. The first attempt was associated with the marginal National-Bolshevik Party (NBP). In 1995, Dugin even contested elections to the State Duma, but he obtained less than one per cent of the vote. His second attempt to get involved in politics is associated with the creation of the Eurasia party in 2002, but already in 2003 the party's other co-founder expelled Dugin from the party.

Since then, Dugin firmly settled on the metapolitical course. Here, "metapolitics" implies pursuing a strategy of modifying the democratic political culture, rather than aiming to participate in the political process directly. This strategy was adopted from the theory of cultural hegemony of Italian communist Antonio Gramsci (1891-1937). The "right-wing Gramscism" stresses the importance of establishing cultural hegemony by making the cultural sphere more susceptible to non-democratic politics through ideology-driven education and cultural production, in preparation for seizing political power by the far right.

Dugin founded the International Eurasian Movement in 2003 and was appointed professor at the Moscow State University in 2008. From 2005 onwards, he also became a popular political commentator who frequently appeared on prime time talk shows and published in influential newspapers. These positions allowed him to bring his Neo-Eurasianist ideas directly to the academic world, whilst using his academic title as a prestigious cover-up for his irrational ideas.

Dugin hailed the ascent of Vladimir Putin. In its turn, the Kremlin clearly perceives Dugin’s ideas as useful. By being regularly present in the public sphere, Dugin and other Russian right-wing extremists extending the boundaries of a legitimate space for illiberal narratives make Russian society more susceptible to Putin’s authoritarianism.

Discussing the relations between Dugin and Putin, I would advise against associating Dugin's Neo-Eurasianism with Putin's right-wing authoritarian kleptocracy. At the same time, three points are worth noting:

1. Dugin’s organisational and intellectual initiatives are integral elements of Putin's authoritarian system. In this role, Dugin joins dozens of other agents of right-wing cultural production who, in one manner or another, contribute to the public legitimisation of Putin's regime.

2. Dugin has worked his way up from the eccentric fringes to the Russian socio-cultural mainstream, but his ideology has not changed since the 1990s. What has radically changed is the Russian mainstream political discourse.

3. While not being directly associated with the Kremlin, Dugin belongs to a circle of individuals that is trying to exert influence on Putin's policies. Russian oligarch Konstantin Malofeev, who has been sanctioned by the EU for sponsoring Russian extremists, including Igor Girkin-Strelkov (sanctioned by the EU and US), involved in separatist activities in Crimea and Eastern Ukraine, belongs to this circle too and apparently provides funds Dugin's initiatives. Dugin, however, is not yet sanctioned either by the EU or US.

Dugin's approach towards Ukraine

Dugin became especially famous in Russia for the Neo-Eurasianist version of classical geopolitics. His book The Foundations of Geopolitics (1997) outlined his political and ideological vision of Russia's place in the world, as well as revisionist and expansionist foreign policy. In that book, he wrote in relation to Ukraine:

Dugin actively supported Russia's invasion of Georgia in 2008 and craved for the complete occupation of that country. For Dugin, the war in Georgia was an existential battle against the West: "If Russia decides not to enter the conflict ... that will be a fatal choice. It will mean that Russia gives up her sovereignty" and "We will have to forget about Sevastopol" [i.e. Ukrainian city situated in Crimea].

Naturally, Dugin fanatically supported the annexation of Crimea in 2014 and urged Putin to invade south-eastern Ukraine.

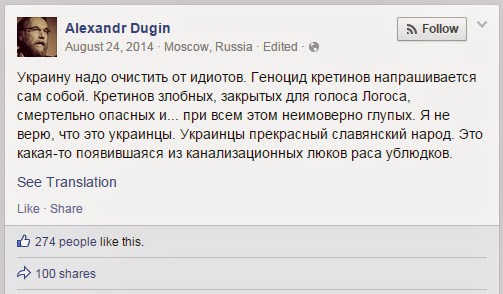

Already at the height of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, in August 2014, Dugin became even more explicit in his hatred of Ukrainians: In a Facebook post dated 24 August 2014, Dugin wrote:

Translation: "Ukraine needs to be cleansed of idiots. A genocide of cretins suggests itself. Cretins who are virulent, closed for the voice of Logos, deadly and ... in addition to this, extremely stupid. I don't believe that these are Ukrainians. Ukrainians are a fine Slavic people. [But] these are some race of bastards that emerged from the sewage".

Dugin's ideology also inspired French and Serbian neo-Eurasianist activists to illegally go to Eastern Ukraine in summer 2014 to kill Ukrainians.

The SYRIZA connection

It is unclear when exactly Dugin established more or less significant contacts with Greek left-wing SYRIZA. Thanks to an e-mail hack by the Anonymous International, it is viable to suggest that these contacts were established with the help of Georgiy Gavrish, director of the marginal Russian Centre of Geopolitical Expertise and a close associate of both Dugin and Malofeev. Gavrish lived in Greece in 2012 and, possibly, 2013.

In 2013, Nikos Kotzias, now Minister of Foreign Affairs in the Alexis Tsipras's cabinet, invited Dugin to deliver a lecture "International Politics and the Eurasianist Vision" on 12 April at the University of Piraeus, where Kotzias held a post of professor of Political Theories. In his lecture, Dugin implicitly suggested that, rather leaving the EU and joining the Russia-led Eurasian Union, Greece should remain in the EU to promote the pro-Russian vision of international politics. The same day, Dugin presented his lecture "The Geopolitics of Russia" at the Panteion University; Konstantinos Filis, research director of the Institute of International Relations at the Panteion University, hosted the event. [This paragraph has been updated, to reflect the fact that Dugin delivered two lectures on the same day, rather than one, as was erroneously stated in the earlier version of the paragraph.]

During his visit to Greece, Dugin also met with SYRIZA's member Dimitris Konstantakopoulos, who also was a correspondent for the Athens News Agency in Moscow (1989-1999). Dugin interviewed Konstantakopoulos, and Konstantakopoulos interviewed him back.

On 18 May 2013, Kotzias, in collaboration with KAPA Research, conducted a public opinion survey on the Greeks' attitude to Russia. Some of the conclusions of the analysis are:

It is unclear who funded or ordered this survey, but two things are known: (1) the survey was not published on the official website of KAPA Research, and (2) the PDF file containing the analysis and results was created on 4 June 2013 and sent by Kotzias to Gavrish on 5 June, together with the original results and raw data from KAPA Research. It seems reasonable to suggest that Malofeev's group ordered and funded the survey via Gavrish or Dugin, in order to test the waters for the promotion of Russian foreign policy in Greece.

After his visit to Greece, Dugin kept in contact with the Greeks and wrote the following:

In December 2013, Dugin wrote a paper "Countries and persons, where there are grounds to create an elite club and/or a group of informational influence through the line of Russia Today". In a footnote, Dugin wrote that, with all these people, he or his representatives "met personally and indirectly or directly talking about a possibility of their participation in the organisational and/or informational initiative of the pro-Russian nature". The paper, in particular, listed Konstakopulousand Alexis Tsipras, the leader of SYRIZA and current Greek Prime Minister. Apart from Dugin's own statement, there is currently no evidence that Dugin or his representatives met with Tsipras, although this might have happened during 2013.

As argued earlier, Dugin is not the person who directly influences the decision-making process in Moscow. Rather, he is a "right-wing ambassador", a representative of Malofeev's group, who gathers information and intelligence and establishes contacts with particular European politicians who may be useful for the promotion of Russia's foreign policy in the EU. Were Russia to influence Greek politics, this would be done through the Greek government's collaboration with the Russian officials. However, Dugin's role in establishing the initial contacts should not be underestimated.

First of all, a few words about Dugin himself (interested readers will find my longer piece on Dugin here, and a thesis on him by my colleague Andreas Umland here).

Who is Dugin?

Dugin's ideology is called Eurasianism, but experts prefer to use the term "Neo-Eurasianism", because Dugin's ideology has a limited relation to Eurasianism, the interwar Russian émigré movement that could be placed in the Slavophile tradition. Rather, Neo-Eurasianism is a mixture of the ideas of French esoteric René Guénon, Italian fascist Julius Evola, National Bolshevism, the European New Right and classical geopolitics.

Dugin attempted to enter Russian political life twice. The first attempt was associated with the marginal National-Bolshevik Party (NBP). In 1995, Dugin even contested elections to the State Duma, but he obtained less than one per cent of the vote. His second attempt to get involved in politics is associated with the creation of the Eurasia party in 2002, but already in 2003 the party's other co-founder expelled Dugin from the party.

|

| Aleksandr Dugin, speaking at the HQ of the National-Bolshevik Party, 1996, Moscow |

Dugin founded the International Eurasian Movement in 2003 and was appointed professor at the Moscow State University in 2008. From 2005 onwards, he also became a popular political commentator who frequently appeared on prime time talk shows and published in influential newspapers. These positions allowed him to bring his Neo-Eurasianist ideas directly to the academic world, whilst using his academic title as a prestigious cover-up for his irrational ideas.

|

| American anti-Semite and former leader of Ku Klux Klan David Duke (left) and Aleksandr Dugin (right) |

Dugin hailed the ascent of Vladimir Putin. In its turn, the Kremlin clearly perceives Dugin’s ideas as useful. By being regularly present in the public sphere, Dugin and other Russian right-wing extremists extending the boundaries of a legitimate space for illiberal narratives make Russian society more susceptible to Putin’s authoritarianism.

Discussing the relations between Dugin and Putin, I would advise against associating Dugin's Neo-Eurasianism with Putin's right-wing authoritarian kleptocracy. At the same time, three points are worth noting:

1. Dugin’s organisational and intellectual initiatives are integral elements of Putin's authoritarian system. In this role, Dugin joins dozens of other agents of right-wing cultural production who, in one manner or another, contribute to the public legitimisation of Putin's regime.

2. Dugin has worked his way up from the eccentric fringes to the Russian socio-cultural mainstream, but his ideology has not changed since the 1990s. What has radically changed is the Russian mainstream political discourse.

3. While not being directly associated with the Kremlin, Dugin belongs to a circle of individuals that is trying to exert influence on Putin's policies. Russian oligarch Konstantin Malofeev, who has been sanctioned by the EU for sponsoring Russian extremists, including Igor Girkin-Strelkov (sanctioned by the EU and US), involved in separatist activities in Crimea and Eastern Ukraine, belongs to this circle too and apparently provides funds Dugin's initiatives. Dugin, however, is not yet sanctioned either by the EU or US.

Dugin's approach towards Ukraine

Dugin became especially famous in Russia for the Neo-Eurasianist version of classical geopolitics. His book The Foundations of Geopolitics (1997) outlined his political and ideological vision of Russia's place in the world, as well as revisionist and expansionist foreign policy. In that book, he wrote in relation to Ukraine:

The sovereignty of Ukraine represents such a negative phenomenon for Russian geopolitics that it can, in principle, easily provoke a military conflict. [...] Ukraine as an independent state with some territorial ambitions constitutes an enormous threat to the whole Eurasia, and without the solution of the Ukrainian problem, it is meaningless to talk about the contitental geopolitics. [...] Considering the fact that a simple intergration of Moscow with Kyiv is impossible and will not result in a stable geopolitical structure [...], Moscow should get actively involved in the re-organisation of the Ukrainian space in accordance to the only logical and natural geopolitical model.In August 2006, Dugin and his Eurasian Youth Union organised a summer camp where right-wing extremists from the Donetsk Republic group (it was involved in organising the initial separatist activities in Eastern Ukraine in 2014) were further indoctrinated and trained to fight against established Ukrainian authorities.

Dugin actively supported Russia's invasion of Georgia in 2008 and craved for the complete occupation of that country. For Dugin, the war in Georgia was an existential battle against the West: "If Russia decides not to enter the conflict ... that will be a fatal choice. It will mean that Russia gives up her sovereignty" and "We will have to forget about Sevastopol" [i.e. Ukrainian city situated in Crimea].

|

| Aleksandr Dugin and his followers in Georgian South Ossetia invaded by the Russian troops in 2008 |

Naturally, Dugin fanatically supported the annexation of Crimea in 2014 and urged Putin to invade south-eastern Ukraine.

Already at the height of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, in August 2014, Dugin became even more explicit in his hatred of Ukrainians: In a Facebook post dated 24 August 2014, Dugin wrote:

Translation: "Ukraine needs to be cleansed of idiots. A genocide of cretins suggests itself. Cretins who are virulent, closed for the voice of Logos, deadly and ... in addition to this, extremely stupid. I don't believe that these are Ukrainians. Ukrainians are a fine Slavic people. [But] these are some race of bastards that emerged from the sewage".

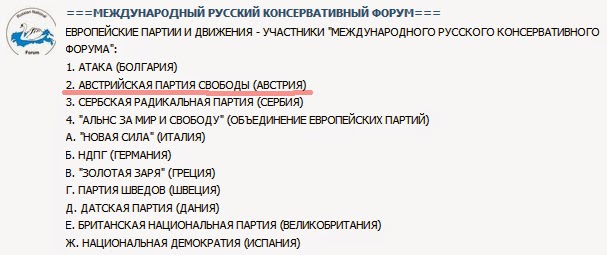

Dugin's ideology also inspired French and Serbian neo-Eurasianist activists to illegally go to Eastern Ukraine in summer 2014 to kill Ukrainians.

The SYRIZA connection

It is unclear when exactly Dugin established more or less significant contacts with Greek left-wing SYRIZA. Thanks to an e-mail hack by the Anonymous International, it is viable to suggest that these contacts were established with the help of Georgiy Gavrish, director of the marginal Russian Centre of Geopolitical Expertise and a close associate of both Dugin and Malofeev. Gavrish lived in Greece in 2012 and, possibly, 2013.

In 2013, Nikos Kotzias, now Minister of Foreign Affairs in the Alexis Tsipras's cabinet, invited Dugin to deliver a lecture "International Politics and the Eurasianist Vision" on 12 April at the University of Piraeus, where Kotzias held a post of professor of Political Theories. In his lecture, Dugin implicitly suggested that, rather leaving the EU and joining the Russia-led Eurasian Union, Greece should remain in the EU to promote the pro-Russian vision of international politics. The same day, Dugin presented his lecture "The Geopolitics of Russia" at the Panteion University; Konstantinos Filis, research director of the Institute of International Relations at the Panteion University, hosted the event. [This paragraph has been updated, to reflect the fact that Dugin delivered two lectures on the same day, rather than one, as was erroneously stated in the earlier version of the paragraph.]

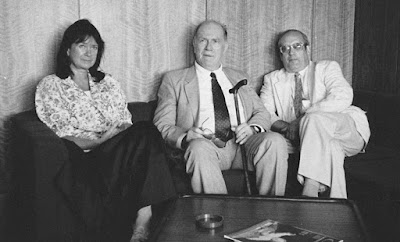

|

| Nikos Kotzias, current Greek Foreign Minister (far left), Aleksandr Dugin (centre) and PhD student Antonis Skotiniotis (far right), 12 April 2013, Piraeus |

|

| Aleksandr Dugin (left) delivers a lecture "The Geopolitics of Russia" co-hosted by Konstantinos Filis (right) |

|

| Aleksandr Dugin (right) interviews SYRIZA's Dimitris Konstantakopoulos (left), April 2013, Greece |

On 18 May 2013, Kotzias, in collaboration with KAPA Research, conducted a public opinion survey on the Greeks' attitude to Russia. Some of the conclusions of the analysis are:

For the Greeks, Russia is a state ally that they trust and want closer relations with. Russia is a strong state, with a perspective for greater growth, with a strong government that the Greeks are in favor. Generally, the Greeks seem to have realised that the world is changing and new forces come into play. [...] Russia, for the Greeks, is a potential military and economic ally that they respect and seem to know relatively well. The new generation is strongly in favor of closer relations with Russia, while the majority shares this view. The Greeks seem to be partly frustrated with their traditional allies in recent years and, therefore, turned to Russia.

It is unclear who funded or ordered this survey, but two things are known: (1) the survey was not published on the official website of KAPA Research, and (2) the PDF file containing the analysis and results was created on 4 June 2013 and sent by Kotzias to Gavrish on 5 June, together with the original results and raw data from KAPA Research. It seems reasonable to suggest that Malofeev's group ordered and funded the survey via Gavrish or Dugin, in order to test the waters for the promotion of Russian foreign policy in Greece.

After his visit to Greece, Dugin kept in contact with the Greeks and wrote the following:

In Greece, our partners could eventually be Leftists from SYRIZA, which refuses Atlanticism, liberalism and the domination of the forces of global finance. As far as I know, SYRIZA is anti-capitalist and it is critical of the global oligarchy that has victimized Greece and Cyprus. The case of SYRIZA is interesting because of its far-Left attitude toward the liberal global system. It is a good sign that such non-conformist forces have appeared on the scene. Dimitris Konstakopulous writes excellent articles and his strategic analysis I find very correct and profound in many cases.In September 2013, Konstakopulous sent to Dugin a position paper that explained why full support should be given to SYRIZA, as well as establishing "the movement of Resistance and Subversion 'Free State'", in response to "a full blown and ruthless War" launched by the "International of the Finance" and "the emerging Totalitarian Empire of Globalization".

In December 2013, Dugin wrote a paper "Countries and persons, where there are grounds to create an elite club and/or a group of informational influence through the line of Russia Today". In a footnote, Dugin wrote that, with all these people, he or his representatives "met personally and indirectly or directly talking about a possibility of their participation in the organisational and/or informational initiative of the pro-Russian nature". The paper, in particular, listed Konstakopulousand Alexis Tsipras, the leader of SYRIZA and current Greek Prime Minister. Apart from Dugin's own statement, there is currently no evidence that Dugin or his representatives met with Tsipras, although this might have happened during 2013.

As argued earlier, Dugin is not the person who directly influences the decision-making process in Moscow. Rather, he is a "right-wing ambassador", a representative of Malofeev's group, who gathers information and intelligence and establishes contacts with particular European politicians who may be useful for the promotion of Russia's foreign policy in the EU. Were Russia to influence Greek politics, this would be done through the Greek government's collaboration with the Russian officials. However, Dugin's role in establishing the initial contacts should not be underestimated.

If you liked this post, you may wish to consider donating to the development of this blog via PayPal.